Can you begin by explaining what the Dhaka Principles are?

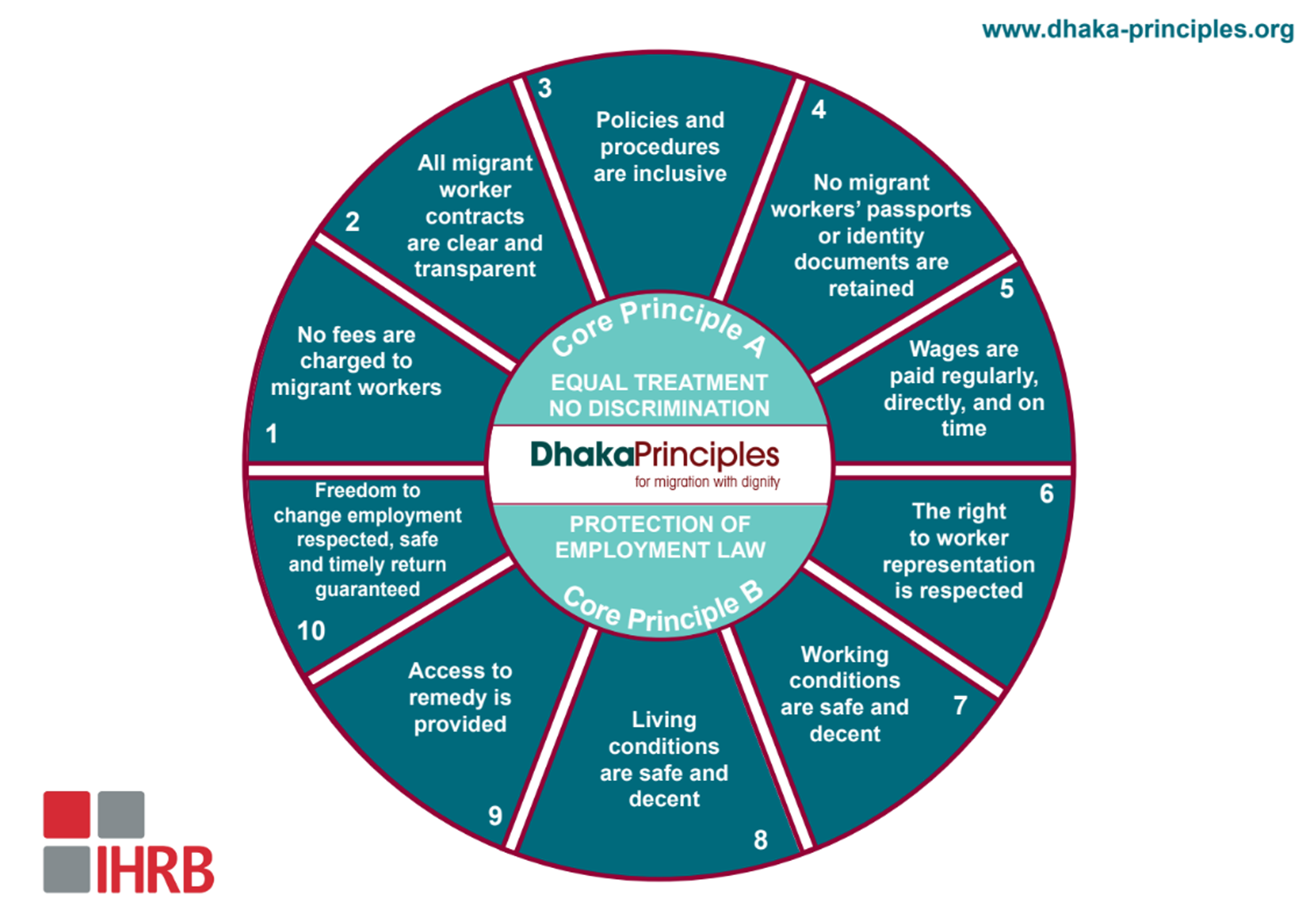

Neill: “We’ve got a number of programmes at the IHRB. The Migrant Workers programme is a significant one and is perhaps what our Institute is the most known for. When we first started researching migrant workers, there was actually quite a lot of useful information out there, but it was all very siloed. The Dhaka Principles were an attempt to pull all that information together and package it in a way that makes it easier for business and other stakeholders to access it. Essentially, we try to make human rights understandable for business. The Dhaka Principles were launched in 2012 as the product of consultations with governments, civil society groups, businesses, and trade unions. They take a worker around the typical migration cycle, which starts with recruitment, to various stages of employment, and then onto their safe return home. Companies will often quote the Dhaka Principles and align their policies with them. They are currently translated into 26 languages.

The Dhaka Principles are a good example of the way we try to operate at the IHRB. They promote human rights best practice and various UN conventions in a way that business can pick them up, understand them and use them. The Dhaka Principles are a foundational part of our programme and have become the framework for all our activities around migrant workers.”

Which one of these ten principles stands out to you as being the most urgent one for businesses to implement currently?

Neill: "All of them are really important and all of them matter at different stages, but for migrant workers it’s nearly always the first principle: No fees are charged to migrant workers. This is also referred to as the Employer Pays Principle. What it means is that no worker should pay for a job, and the cost of recruitment should be borne not by the worker but by the employer. Recruitment fees include travel, passports, visa processing, writing CVs, anything else connected to the work. There is a cost associated with recruitment, but it should be a business cost.

Very often all the promises made to migrant workers about how much they’ll earn, how much overtime there is, paying off recruitment fees in a few months’ time - all those promises fall to dust the minute the worker gets abroad. Very often, workers will return home and they would have hardly earned any money at all, some might even be in negative equity. That’s why for migrant workers this recruitment fee issue is so significant. It loads this vulnerability onto migrant workers right from the beginning of their experience.

If standards get raised for migrant workers abroad, it should in theory improve standards at home because companies at home would have to compete for those workers. If one standard raises, the other should, and vice versa, but we don’t always see that.”

Could you speak about how gender plays into labour exploitation?

Neill: “There will always be challenges that women workers face that men workers do not. It’s important that you call it out in your company and undertake additional assessment on the specific challenges that women workers may face. Make sure that there are ways for women to access redress or grievance mechanisms and make sure that those are appropriate. Women workers may not want to approach a male representative about a particular issue or talk about gender violence or harassment. You need to have a gender lens when you’re setting up your processes.

What’s interesting is that a lot of the gaps seem to be around human resources, not only human rights. Do you have managers in place that are aware of the challenges that women migrant workers might face? What does your employee handbook include? Do your women workers have access to women trade union officials? Having the right person in place is a very obvious and important measure.

Recently, we’ve undertaken a gender review of the Dhaka Principles. We felt that we weren’t including women migrant workers enough in our work.” Based on our research we will launch a new version of the implementation guidance for the Dhaka Principles on International Women’s Day 8th March 2024.

There are a number of recent conflicts and instabilities around the world – wars, public health crises like Covid-19, climate disasters. How do these impact migration and exploitation?

Neill: “Conflict anywhere will always create a movement of people. People might also flee to make a living because they can no longer do so where they are. With the climate crisis, traditional farming may become unsustainable, you can get flooding, inundation, extreme weather events or salination. Then there’s the economic shocks of the climate crisis. Some old and carbon-heavy industries like mining have begun to close down. Mining employs many low-wage workers, many of whom are migrants. A mine is also location-specific since it supports the surrounding community: a mine that employs 10 000 people might be supporting 50 000 people in that location. These populations are going to be on the move with their families, and they are primarily going to move to towns. There are impacts there for social cohesion. We see these influxes of migrants, how can they be accommodated into the global order?

The Ukraine war is another example of this type of domino effect. In England, many workers used to come from Bulgaria, Romania, and the Czech Republic, to work on farms and in horticulture. Now they can’t do that as easily after Brexit. British farms started making complex arrangements for Ukrainian workers to come and take their those jobs, which shows the ridiculousness of arguments for Brexit. We were still going to be totally and utterly dependent on migrant workers, just from a different country of origin. Of course once the conflict started no new Ukranian workers came and many of those already employed left to return to fight. Farmers in the UK are now having to look even further abroad.

It always amuses me when I read the happiness indexes that various organisations do, and often Finland is quite high, alongside Denmark, Sweden and Norway. And you have to think, but who’s managing the sewage plants? Who’s mending the roads? Who’s sweeping the streets? Peoples’ standard of living is maintained on the back of migrant worker populations. We need to have more honest conversations about the needs of societies and how these things can be managed.”

Discover the Dhaka Principles here.

Find reports, podcasts, and commentary from the IHRB’s Migrant Workers programme here.

Interview prepared by Emma de Carvalho